NewsBot

New Member

- Messages

- 111,281

- Reaction score

- 2,947

Brush up on your capology skills in anticipation of the various moves the Cowboys will make in an effort to get under the cap by March 11.

Late last night, news broke that the Cowboys had restructured the contracts of Orlando Scandrick and Sean Lee, creating some much-needed cap space. Tony Romo followed early this morning, and there may be more moves in store for the Cowboys. The Cowboys are not alone in doing this, as teams around the league have to do some creative accounting to get under the salary cap by March 11. For most teams, this will mean restructuring contracts, signing cap-friendly contract extensions, asking players to take pay cuts or downright releasing players. The Dallas Cowboys will likely have to do a little bit of everything to get under the cap.

Over the next few days, you'll hear lots of numbers about player salaries, prorated signing bonuses, dead money, cap hits and more. To get you ready for that, we offer you this primer on the basics of salary cap management, and we'll walk through most of the moves the Cowboys are likely going to make over the coming days.

Our life as football fans would be so much easier if the NFL had a hard salary cap. A hard cap would be a maximum amount, say this year's $133 million, that teams would not be allowed to exceed. End of discussion.

But that wouldn't be any fun now, would it?

The NFL softened up its cap by allowing signing bonuses to be spread out over the life of a contract. In salary cap terms, signing bonuses are prorated over the length of a contract, as described in the CBA:

CBA, Article 16, Section 6, Paragraph 5: Proration: The total amount of any signing bonus shall be prorated over the term of the Player Contract (on a straight-line basis, unless subject to acceleration or some other treatment as provided in this Agreement), with a maximum proration of five years, in determining Team Salary and Salary.

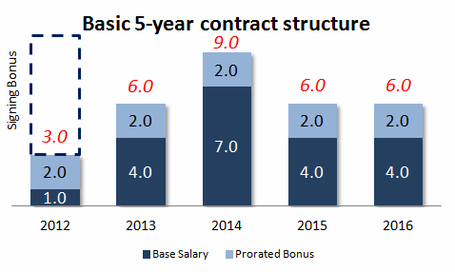

For this primer, we'll use one basic contract to walk through the different salary cap options teams have. Sticking to one contract makes the different options easier to understand, and makes the differences between the presented options more readily apparent. Our basic contract will be a 5-year, $30 million contract, $10 million of which the player receives as a signing bonus. For salary cap purposes, that contract could look as follows:

Signing bonuses are paid out immediately, so the player would get his $10 million signing bonus right away. Add $1 million in base salary for year one (in this case, 2012) and our fictitious player walks home with $11 million in real money for the first season of his contract.

But for salary cap purposes, the full amount of the signing bonus doesn't count against the cap immediately. Instead, it is prorated over five years. In this example, that adds $2 million to the player's cap amount for each of the five years of his contract. The yearly cap charge (the red figures in the graph above) for our player is his base salary in a given year plus the prorated bonus allocated to that specific year.

The basic contract we are using would be described as a "cap-friendly contract," because the team is backloading the contract by pushing more money into the outer years, and the contract is designed to be restructured in 2014, but more on that later.

Let's now assume that after the 2013 season, the team decides it wants to change the player's contract. This can be for any number of reasons: the team needs cap space in 2014, the player is under-performing his contract or some other reason. This happens to NFL teams all the time. The Cowboys find themselves in this position with a number of contracts this offseason. And like all other teams, they have basically three options: restructure the contract, cut the player or renegotiate the contract. All of which we'll look at below.

Restructured Contract (Tony Romo, Sean Lee & Orlando Scandrick):

We will use our fictitious player to look at what the Cowboys did with Scandrick and Lee yesterday. Our fictitious player counts $9 million against the 2014 cap, with a $7 million base salary and a $2 million prorated cap charge from the signing bonus paid out in 2012. From the beginning of the contract, 2014 was meant as a year in which a restructure could take place, if the team needed the money. NFL contracts often contain language that gives the teams full discretion over such a restructure, making them almost automatic.

In our case, the team needs to create cap space, so it restructures the contract by converting $6 million of the player's 2014 base salary into a signing bonus.

The benefit for the player is that $6 million of his 2014 salary is turned into a signing bonus, and therefore guaranteed. The benefit for the team is that it can once again prorate that signing bonus over the remaining years of the contract, as the following graph shows:

By restructuring the contract, the team has lowered the player's 2014 base salary from $7 to $1 million by converting $6 million of the original base salary into a signing bonus. That $6 million signing bonus (marked here in yellow as 'Prorated Bonus 2') is prorated over the remaining three years at $2 million each year. Versus the original contract, the team lowered its 2014 cap charge from $9 million to $5 million and created $4 million in cap space. However, the team also increased its cap charge for 2015-16 by $2 million each year.

This type of contract restructuring is a no-brainer for the player. He doesn't lose any money at all, and even gets a large part of his 2014 salary guaranteed because it's now a signing bonus. However, the language used around the NFL is pretty sloppy when it comes to restructuring contracts, because the word 'restructuring' is also often used to describe a situation where a player is asked to take a pay cut, which should accurately be called a renegotiated or reworked contract.

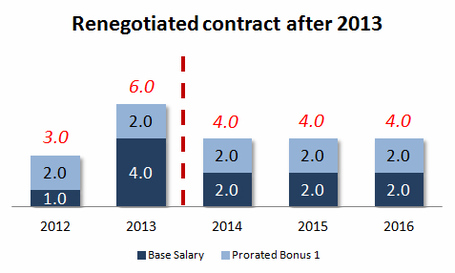

Renegotiated Contract (DeMarcus Ware)

In this situation, the team is unhappy with the contract it has signed with the player, and asks the player to take a pay cut. This goes beyond a simple restructuring of an existing contract. The two sides, team and player, have to renegotiate and agree to a new or reworked contract at a lower salary. This is what that could look like for our fictitious player:

This looks a lot easier than it is in real life. In our example, the team and the player agree that $7 million in 2014 and $4 million each in 2015 and 2016 are too much, and agree to a pay cut that reduces the player's base salary to $2 million per year.

In our example, this saves the team $9 million in real money, and reduces the cap hit in 2014 by $5 million and $2 million each in 2015 and 2016. Importantly, the team remains on the hook for the cap hit from the unamortized part of the original signing bonus. If the player doesn't agree to the proposed pay cut, the team has the option of releasing him or trading him.

A real-life example of this happened last year when Doug Free agreed to a pay cut. Free was scheduled to make $7 million in 2013 and count $10.02 million against the cap. Free and the Cowboys renegotiated a contract that lowered Free's salary to $3.5 million for 2013 and for 2014. In return for the new contract, Free was guaranteed his 2013 salary, which previously was not guaranteed.

Cowboys 2011-2017 Salary Cap Health Manifesto

KD Drummond

Dallas Cowboys "cap mismanagement" seems to be a trending topic recently. We'll explain why it just isn't so.

Cowboys 2011-2017 Salary Cap Health Manifesto

The Cowboys will have to take a similar approach with DeMarcus Ware. Ware is scheduled to get a base salary of $12.2 million in 2014 ($16 million cap hit) and $13.8 million in 2015 ($17.5 million cap hit), 2016 and 2017 are voidable years in Ware's contract. The Cowboys will make Ware an offer with a lower base salary. In return for accepting a lower salary, the Cowboys will offer to guarantee all or part of his salary over the two years. Additionally, they will likely add incentives to Ware's contract that would allow him to regain at least part of the lost salary if he reaches certain incentives.

In the NFL, incentives are classified as "Likely To Be Earned" and "Not Likely To Be Earned". LTBEs count against the cap, NLTBEs don’t. Instead, the NLTBE incentives are applied to the cap retroactively after the season. Also, and importantly for Ware's possible new contract, NLTBEs are based on the previous year’s performance, per the CBA:

"Any team performance will be automatically deemed to be "Likely to be earned" if the Team met or exceeded the specified performance during the prior League Year, and will be automatically deemed to be "not likely to be earned" if the Team did not meet the specified performance during the prior League Year."

Effectively, any 2014 incentives in Ware's new contract with higher thresholds than Ware’s 2013 individual statistical achievements are automatically classified as NLTBE - and don't count against the 2014 cap.

In Ware’s case, that 2013 performance bar would be pretty low: Six sacks, 28 tackles and 648 snaps – all career lows. Even the number of starts (13) and a Pro Bowl berth (none) could be incentivized.

Somewhere in that mix of reduced salaries, guaranteed money and incentives is a solution that will allow Ware to stay with the Cowboys without losing face.

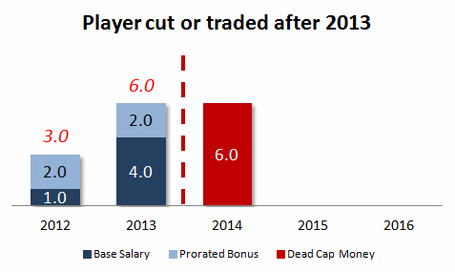

Player cut, traded or retires (Phil Costa? Kyle Orton?)

If a player is cut before the end of his contract, the entire unamortized signing bonus money (the remaining prorated bonus money) accelerates immediately and counts against the 2014 salary cap.

The same rule applies when a player is traded or retires. The unamortized signing bonus remaining on the player's contract accelerates into his old team's salary cap in 2014. In the case of a trade, the new team takes no cap hit whatsoever. In our example, the $6 million remaining unamortized signing bonus accelerates immediately as follows:

In essence, trading or cutting a player saves the old team from paying the player's base salary, but that comes at the price of taking a cap hit by having to account for the full accelerated signing bonus. In our example, cutting the player saves the team $3 million in cap space in 2014.

The money left on the cap from the cap hit teams take by cutting players is called dead money. In this example, the team would be left with $6 million of dead money on their 2014 cap. But the team has an additional option at its disposal.

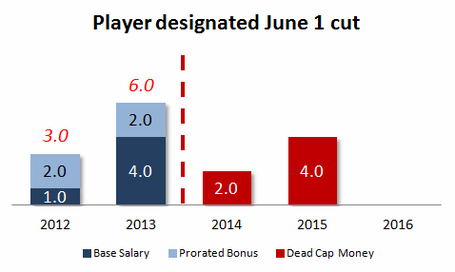

June 1 cuts (Miles Austin)

If a player is cut before June 1, 2014, the remaining signing bonus accelerates immediately and counts against the 2014 salary cap. But if a player is cut after June 1 this year (or designated a "June 1 cut"), only the 2014 part of the unamortized signing bonus counts against the cap in 2014, while the remainder counts against the 2015 cap. Teams can designate up to two players as "June 1 cuts" even if they cut them before June 1, 2014. This is what the cap situation would look like if our fictitious player was designated a June 1 cut:

By designating the player a June 1 cut, the team lowers its 2014 cap hit to $2 million, but will have $4 million in dead money counting against its 2015 cap.

In the real-life example of Miles Austin, Austin carries a cap figure of $8.249 million in 2014. If Austin were to be made a June 1 cut, his cap hit would be lowered to $2.749 million (the proration for 2014), thus creating $5.5 million in cap space. However, that move would also leave the Cowboys with $5.1 million in dead money in 2015.

We've seen that a team has a variety of options for lowering its cap hit. In our examples, an original cap hit of $9 million was reduced to $6, $5, $4, and $2 million with a variety of different measures.

The salary cap was initially designed to limit the amount of money a team can spend on player salaries. But teams quickly recognized that the best way to stay under the cap was by working around it. One way of doing this is by backloading contracts and pushing chunks of salaries into future years with the expectation that a rising cap in future years will create more room under the cap.

The Cowboys have traditionally tried to use every last dollar of the cap to their advantage. It is, if you will, part of the Cowboys business model, part of the way they do business, just like some real-life companies have a high gearing ratio (a high proportion of debt to equity) and others have a low gearing ratio (a low proportion of debt to equity). The Cowboys do this in part because - in contrast to many other teams who see skimping on player salaries as a source of profit (the less salary you pay, the higher your profit) - the Cowboys generate enough profit in other parts of the franchise to not have to worry about turning a profit on player salaries.

In summary, it's funny how we as sports fans collectively get hung up so much on discussing accounting procedures. The salary cap is an accounting tool aggressively used by Cowboys, which often leads to the perception that the Cowboys are in "cap hell". They are not. What they are instead is a team that overspends but underperforms relative to its competitors.

And that is the much bigger issue.

Continue reading...