Concord

Mr. Buckeye

- Messages

- 12,825

- Reaction score

- 119

Former Steelers broadcaster, Terrible Towel creator Cope dies

PITTSBURGH -- Myron Cope spoke in a language and with a voice never before heard in a broadcast booth, yet a loving Pittsburgh understood him perfectly during an unprecedented 35 years as a Steelers announcer.

The screechy-voiced Cope, a writer by trade and an announcer by accident whose colorful catch phrases and twirling Terrible Towel became nationally known symbols of the Steelers, died Wednesday at age 79.

Cope died at a nursing home in Mount Lebanon, a Pittsburgh suburb, Joe Gordon, a former Steelers executive and a longtime friend of Cope's, said. Cope had been treated for respiratory problems and heart failure in recent months.

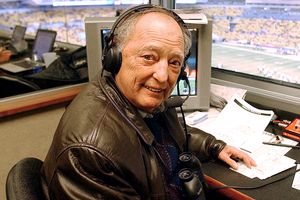

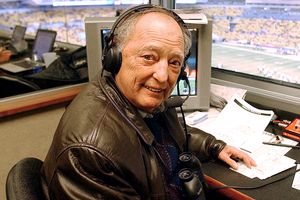

Myron Cope's popularity extended beyond the broadcast booth, as Steelers fans embraced him and his unique play-calling.

Cope's tenure from 1970-2004 as the color analyst on the Steelers' radio network is the longest in NFL history for a broadcaster with a single team and led to his induction into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2005.

"His memorable voice and unique broadcasting style became synonymous with Steelers football," team president Art Rooney II said Wednesday. "They say imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and no Pittsburgh broadcaster was impersonated more than Myron."

One of Pittsburgh's most colorful and recognizable personalities, Cope was best known beyond the city's three rivers for the yellow cloth twirled by fans as a good luck charm at Steelers games since the mid-1970s.

The Terrible Towel is arguably the best-known fan symbol of any major pro sports team, has raised millions of dollars for charity and is displayed at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Upon Cope's retirement in 2005, team chairman Dan Rooney said, "You were really part of it. You were part of the team. The Terrible Towel many times got us over the goal line."

Even after retiring, Cope -- a sports talk show host for 23 years -- continued to appear in numerous radio, TV and print ads, emblematic of a local popularity that sometimes surpassed that of the stars he covered.

Team officials marveled how Cope received more attention than the players or coaches when the Steelers checked into hotels, accompanied by crowds of fans so large that security guards were needed in every city.

"It is a very sad day, but Myron lived every day to make people happy, to use his great sense of humor to dissect the various issues of the sporting world. ... He's a legend," former Steelers Pro Bowl linebacker Andy Russell said.

Cope didn't become a football announcer until age 40, spending the first half of his professional career as a sports writer. He was hired by the Steelers in 1970, several years after he began doing TV sports commentary on the whim of WTAE-TV program director Don Shafer, mostly to help increase attention and attendance as the Steelers moved into Three Rivers Stadium.

Coincidentally, a pair of rookies -- Cope and a quarterback named Terry Bradshaw -- made their Steelers debuts during the team's first regular season game at Three Rivers on Sept. 20, 1970.

Neither Steelers owner Art Rooney nor Cope had any idea how much impact he would have on the franchise. Within two years of his hiring, Pittsburgh would begin a string of home sellouts that continues to this day, a stretch that includes five Super Bowl titles.

Cope became so popular that the Steelers didn't try to replace his unique perspective and top-of-the-lungs vocal histrionics when he retired, instead downsizing from a three-man announcing team to a two-man booth.

Just as Pirates fans once did with longtime broadcaster Bob Prince, Steelers fans began tuning in to hear what wacky stunt or colorful phrase Cope would come up with next. With a voice beyond imitation -- a falsetto so shrill it could pierce even the din of a touchdown celebration -- Cope was a man of many words, some not in any dictionary.

To Cope, an exceptional play rated a "Yoi!" A coach's doublespeak was "garganzola." The despised rival to the north was always the Cleve Brownies, never the Cleveland Browns.

Cope gave four-time Super Bowl champion coach Chuck Noll the only nickname that ever stuck, the Emperor Chaz. For years, Cope laughed off the downriver and often downtrodden Cincinnati Bengals as the Bungles, though never with a malice or nastiness that would create longstanding anger.

Among those longtime listeners was a Pittsburgh high school star turned NFL player turned Steelers coach -- Bill Cowher.

"My dad would listen to his talk show and I would think, 'Why would you listen to that?' " Cowher said. "Then I found myself listening to that. I [did] my show with him, and he makes ME feel young."

Cope, who was born Myron Kopelman, was preceded in death by his wife, Mildred, in 1994. He is survived by a daughter, Elizabeth, and a son, Daniel, who is autistic and lives at Allegheny Valley School, which received all rights to the Terrible Towel in 1996. Another daughter, Martha Ann, died shortly after birth.

http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/news/story?id=3266796

PITTSBURGH -- Myron Cope spoke in a language and with a voice never before heard in a broadcast booth, yet a loving Pittsburgh understood him perfectly during an unprecedented 35 years as a Steelers announcer.

The screechy-voiced Cope, a writer by trade and an announcer by accident whose colorful catch phrases and twirling Terrible Towel became nationally known symbols of the Steelers, died Wednesday at age 79.

Cope died at a nursing home in Mount Lebanon, a Pittsburgh suburb, Joe Gordon, a former Steelers executive and a longtime friend of Cope's, said. Cope had been treated for respiratory problems and heart failure in recent months.

Myron Cope's popularity extended beyond the broadcast booth, as Steelers fans embraced him and his unique play-calling.

Cope's tenure from 1970-2004 as the color analyst on the Steelers' radio network is the longest in NFL history for a broadcaster with a single team and led to his induction into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2005.

"His memorable voice and unique broadcasting style became synonymous with Steelers football," team president Art Rooney II said Wednesday. "They say imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and no Pittsburgh broadcaster was impersonated more than Myron."

One of Pittsburgh's most colorful and recognizable personalities, Cope was best known beyond the city's three rivers for the yellow cloth twirled by fans as a good luck charm at Steelers games since the mid-1970s.

The Terrible Towel is arguably the best-known fan symbol of any major pro sports team, has raised millions of dollars for charity and is displayed at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Upon Cope's retirement in 2005, team chairman Dan Rooney said, "You were really part of it. You were part of the team. The Terrible Towel many times got us over the goal line."

Even after retiring, Cope -- a sports talk show host for 23 years -- continued to appear in numerous radio, TV and print ads, emblematic of a local popularity that sometimes surpassed that of the stars he covered.

Team officials marveled how Cope received more attention than the players or coaches when the Steelers checked into hotels, accompanied by crowds of fans so large that security guards were needed in every city.

"It is a very sad day, but Myron lived every day to make people happy, to use his great sense of humor to dissect the various issues of the sporting world. ... He's a legend," former Steelers Pro Bowl linebacker Andy Russell said.

Cope didn't become a football announcer until age 40, spending the first half of his professional career as a sports writer. He was hired by the Steelers in 1970, several years after he began doing TV sports commentary on the whim of WTAE-TV program director Don Shafer, mostly to help increase attention and attendance as the Steelers moved into Three Rivers Stadium.

Coincidentally, a pair of rookies -- Cope and a quarterback named Terry Bradshaw -- made their Steelers debuts during the team's first regular season game at Three Rivers on Sept. 20, 1970.

Neither Steelers owner Art Rooney nor Cope had any idea how much impact he would have on the franchise. Within two years of his hiring, Pittsburgh would begin a string of home sellouts that continues to this day, a stretch that includes five Super Bowl titles.

Cope became so popular that the Steelers didn't try to replace his unique perspective and top-of-the-lungs vocal histrionics when he retired, instead downsizing from a three-man announcing team to a two-man booth.

Just as Pirates fans once did with longtime broadcaster Bob Prince, Steelers fans began tuning in to hear what wacky stunt or colorful phrase Cope would come up with next. With a voice beyond imitation -- a falsetto so shrill it could pierce even the din of a touchdown celebration -- Cope was a man of many words, some not in any dictionary.

To Cope, an exceptional play rated a "Yoi!" A coach's doublespeak was "garganzola." The despised rival to the north was always the Cleve Brownies, never the Cleveland Browns.

Cope gave four-time Super Bowl champion coach Chuck Noll the only nickname that ever stuck, the Emperor Chaz. For years, Cope laughed off the downriver and often downtrodden Cincinnati Bengals as the Bungles, though never with a malice or nastiness that would create longstanding anger.

Among those longtime listeners was a Pittsburgh high school star turned NFL player turned Steelers coach -- Bill Cowher.

"My dad would listen to his talk show and I would think, 'Why would you listen to that?' " Cowher said. "Then I found myself listening to that. I [did] my show with him, and he makes ME feel young."

Cope, who was born Myron Kopelman, was preceded in death by his wife, Mildred, in 1994. He is survived by a daughter, Elizabeth, and a son, Daniel, who is autistic and lives at Allegheny Valley School, which received all rights to the Terrible Towel in 1996. Another daughter, Martha Ann, died shortly after birth.

http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/news/story?id=3266796