This option largely comes down to a woman named Lisa Friel, whose league office is adorned with portraits of giants: the former Giants quarterback Phil Simms, the current Giants quarterback Eli Manning — and, most tellingly, Robert M. Morgenthau, the august former Manhattan district attorney.

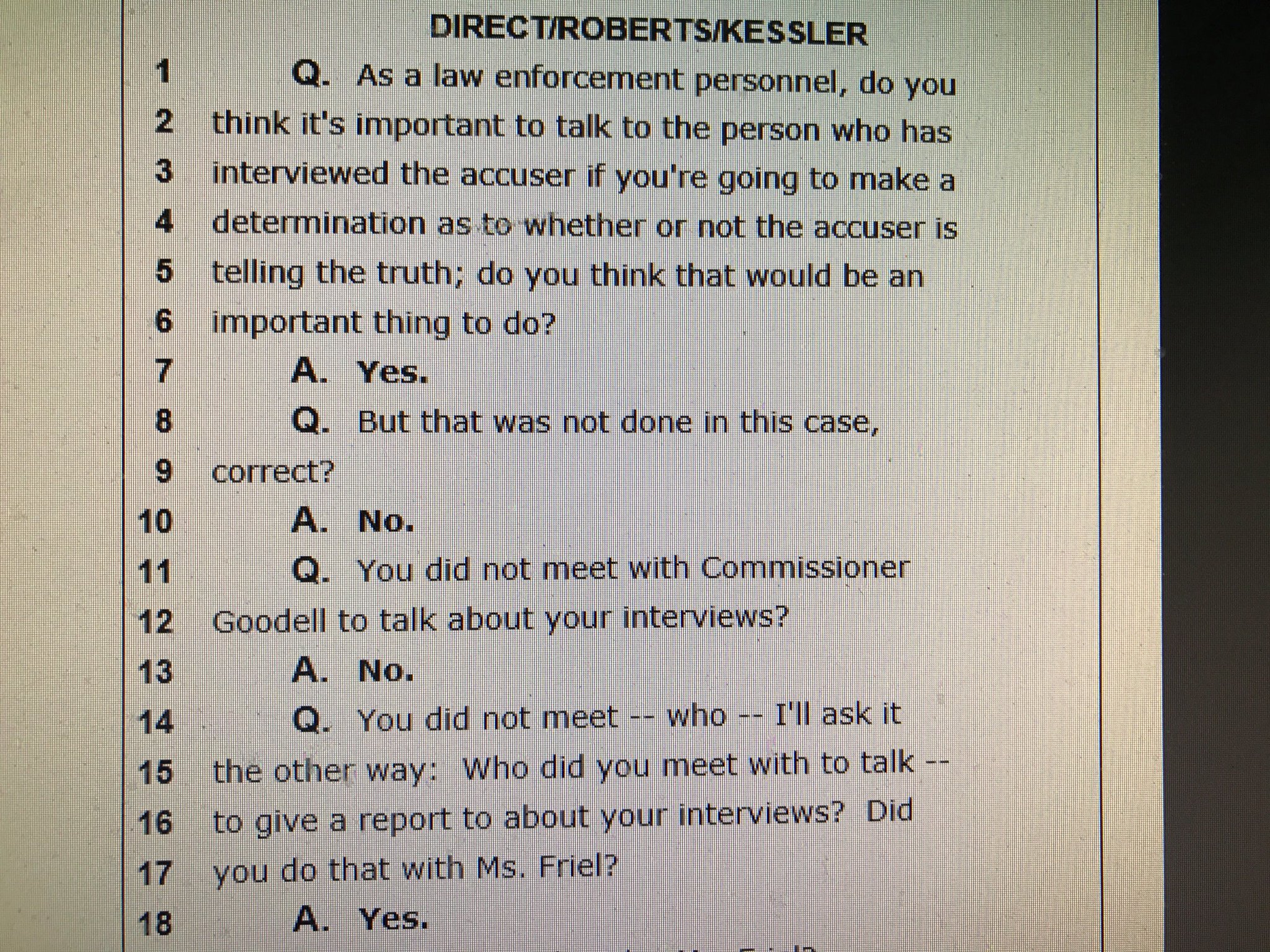

Friel spent nearly three decades working for Morgenthau, serving for many years as the chief of his Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit. She said he had instilled in her a prosecutorial code of conduct: “You investigate every allegation that comes in; you investigate it objectively, sensitively and thoroughly. And when you get to the end of your investigation, you make an objective decision about what happened. That’s your job.”

Friel said she was applying those principles as the

N.F.L.’s senior vice president for investigations — a position created in the wake of the league’s mishandling of the case of Ray Rice, then a Baltimore Ravens running back, whose chilling assault of his future wife was captured on surveillance video and became, among other things, a public relations disaster for the N.F.L.

Friel is responsible for investigating alleged violations of the league’s personal conduct code: domestic violence, sexual assault, animal cruelty, blackmail, extortion, racketeering, disorderly conduct, you name it. She emphasizes that the adjudications or dismissals of court cases do not dictate the outcomes of her own inquiries, which some officials in the players’ union find at times to be overzealous.

This means, for example, that even though Jets linebacker Sheldon Richardson pleaded guilty last month to speeding, running a red light and resisting arrest in connection with that Bentley episode — and even though he was fined $1,050 and sentenced to 100 hours of community service — the matter is not necessarily over, as far as the N.F.L. is concerned.

“We’re looking at whether his actions violated our workplace conduct policy, so we’re going to consider all the facts and circumstances,” Friel said. “Stay tuned.”

Her job, which is intended to establish much-needed consistency in the league’s handling of misconduct cases, is at the center of a decidedly alpha-male environment. But Friel, 58, sees it as a twinning of passions, “a perfect fit.”

To begin with, she is a devout Giants fan, a season-ticket holder whose basement in her Brooklyn apartment is, as The Daily Beast once reported, a blue-and-red shrine to the Jints. Among her earliest memories of growing up in New Jersey is watching a Giants game on a black-and-white television and asking her father: “Who are we rooting for, Daddy? The ones in the black uniforms or the ones in the white uniforms?”

Then there is her professional background. In addition to her 28 years with the district attorney’s office — a time memorialized on her office wall by a framed courtroom sketch of her in full prosecution mode — Friel worked for a security company as a vice president for a division specializing in investigating and consulting on sexual misconduct.In taking the position with the N.F.L., Friel said, she saw another opportunity “to do something that really mattered.” But in the curlicue way of fate, she owes her job to Rice.

Outra